by Director of Promise City Programs and Partnerships Liz Cortez

The Mission Promise Neighborhood (MPN) team is honored to present at the 2022 StriveTogether Convening in Chicago. The title of our session is “Listen and Follow While the Community Leads.” In this session, Parent and Youth Engagement Specialist Ana Avilez and Associate Director of Data and Learning Michelle Reiss-Top will share lessons learned from the engagement of parents and youth in a human-centered design process to co-create a community report card that focuses on systems barriers and fosters our community’s ownership of data to influence systemic change.

StriveTogether, of which MPN has been a member since 2018, is a national network that supports cradle-to-career initiatives (providing prenatal to career services) across the country by providing technical assistance to backbone teams working to achieve systems transformation in their communities. StriveTogether has challenged our initiative to collect and analyze data that addresses systemic inequities. Traditionally, the main focus of our data collection across our partnership has been on behavior change of the individual (child, youth and parent) and academic scores. In addition to these traditional metrics, we are interested in developing actionable systems indicators that will help us advocate for shifting policies, practices, resources and power structures that produce more equitable prenatal-to-career outcomes in our community. This is the focus of our MPN community report card.

“Those closest to the problem are closest to the solution.”

– Community Partner

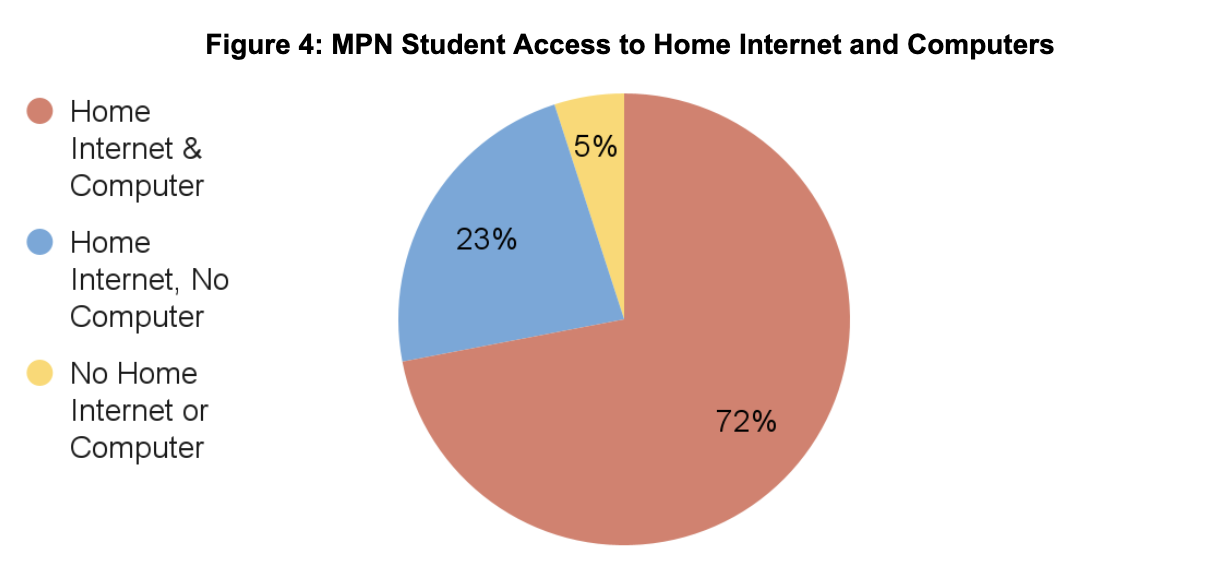

Toward the end of 2021, MPN began engaging parents and youth using the human-centered design approach. A design team comprising parents, youth and staff began a dialogue with community members and collected information via one-on-one interviews and in focus groups. To work together in a virtual format due to pandemic challenges, we provided design team members with capacity-building around using both Zoom and the Miro collaborative platform, plus we surveyed members for any technology equipment needs.

Our meetings always started with the proposition that we would co-create something that would reflect the needs and desires of the community – and that we were open to what the group would come up with in terms of what it should look like. Parents and youth became researchers and developed the questions we would ask our community through one-on-one interviews and focus groups. After those interactions, interviewers from the design team had the opportunity to share the stories they were collecting: We started to see emerging themes.

“I appreciated having a dialogue with my community rather than collecting feedback through a survey.”

– Design Team Member

From surviving to thriving

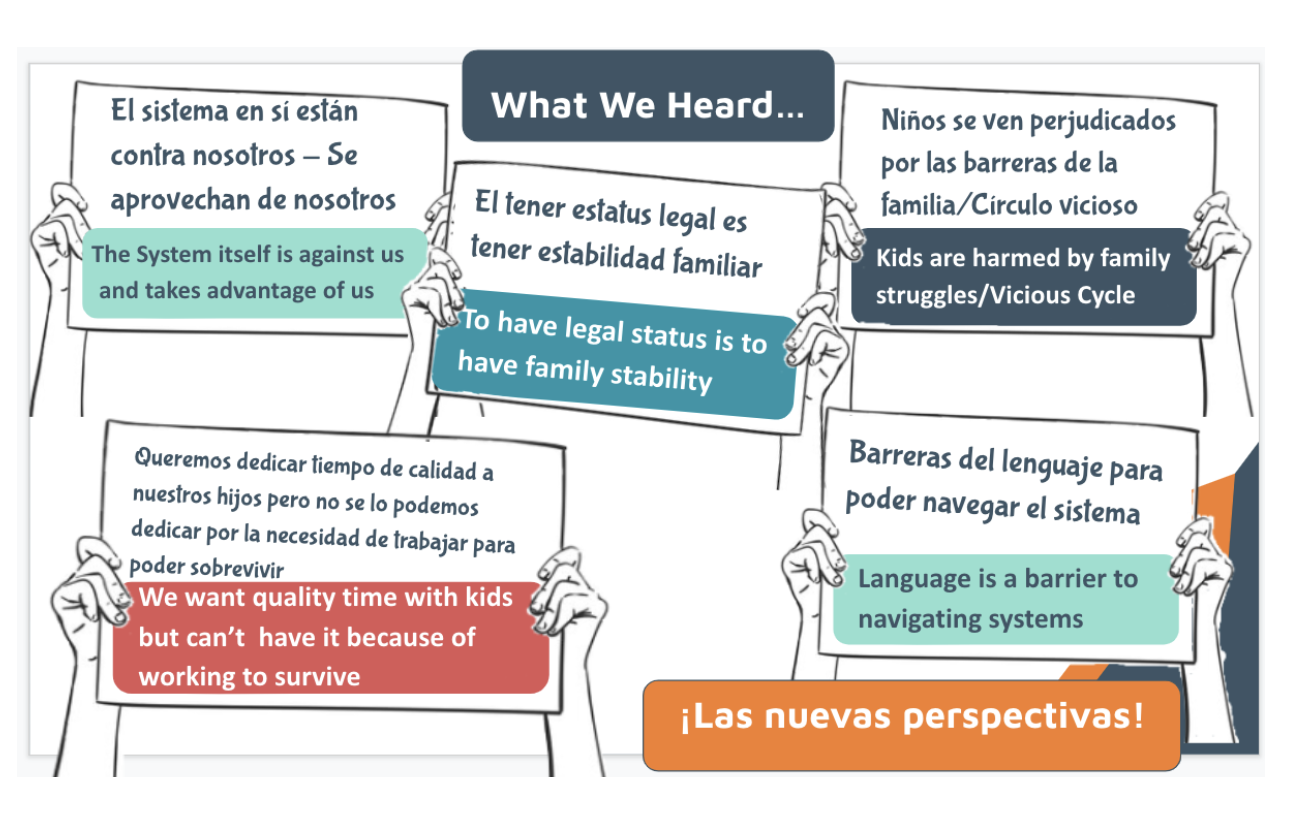

We learned much about what our community members are experiencing when navigating systems, especially during the pandemic. Families are concerned about academic outcomes, but shared that many needs are not being addressed, creating barriers to students and families thriving. After analyzing all the information we gathered, we developed key insights that reflect our families’ needs and barriers.

Families shared that the system works against them and even takes advantage of them. The ability to obtain legal status is at the center of whether a family can thrive. Without such legal status, coupled with English-language skills to navigate systems (e.g., schools, city agencies, employment), parents are compelled to work more than one job and cannot spend quality time with their kids, with the latter harmed by this vicious cycle.

“Who is asking these questions? I’ve never been asked about my story.”

– Community Member

Families shared that they are experiencing survey and intake fatigue. Every institution that they navigate is asking them the same questions. They also shared that they rarely get feedback: They are curious about how things are changing in the community, but the data is not coming back to the community members to make sense of it. Consequently, we thought it was important that whatever we created to demonstrate community needs and desires should be immediately available to the community.

Prototype development: An MPN App to collect community data

After months of working collaboratively, we devised an App prototype that would allow us to collect community data on barriers and desires. Our App is in the pilot stage and includes questions about community members’ experiences as they navigate systems ranging from city agencies and community-based organizations to schools and others. Additionally, the App will be a place where community members can access videos and listen to stories that community members are sharing about their experiences, needs and desires. The App will provide community members with access to the data right after completing the surveys. They can see what other community members are saying and use the data in any leadership space they are in to advocate for their needs and those of the community.

Next steps

We have just begun the data collection through the App. We envision coding the data to develop systems-level indicators that will be tracked over time and used to paint a picture of what the community is experiencing and to begin a planning process with our community partners and parents, and youth around strategies and advocacy. We envision that families will have the data that they need to advocate for their needs and help to change the systems that are not working for them.

Stay tuned for the next exciting phase of our work.

______________________________

Community Report Card Design Team Members:

Rosario R., Parent

Abril M., College Student

Jacqueline R., Parent

Maria G., Parent

Margarita G., Parent

Osiris L., Parent

Jacqueline H., Parent

Erick J., High School Student

Michelle Reiss-Top, Associate Director of Data and Learning

Ana Avilez, Parent and Youth Engagement Specialist

Alejandro Bautista Zugaide, Family Success Coach

Susana Gil-Duran, Early Learning Family Success Coach

Liz Cortez, Director of Promise City Programs and Partnerships