by Evaluation Fellow Maria Dominguez

Every year, Mission Promise Neighborhood (MPN) administers the School Climate Survey (SCS) to middle and high school students who go to schools in the MPN footprint and participate in onsite programs that are part of the MPN service network. We are pleased to share the key findings from the spring 2022 survey.

This is the first time MPN has been able to administer the survey in three years, due to the challenges of distance learning and families’ urgent resource needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Two MPN partners, Jamestown and Mission Graduates, administered the survey via SurveyMonkey to students at their on-campus Beacon Centers in May 2022.

The SCS has several purposes. The US Department of Education, which has funded MPN since 2012, requires us to report annually on community indicators that we track through the SCS. Findings from the SCS also support our network partners and community members: By hearing directly from our students, the MPN network can leverage our best practices and improve upon our service model. Hearing student perspectives also amplifies the needs of young community members to our elected officials and other key stakeholders.

This year, 153 students across four MPN schools[1] – Everett Middle School, Buena Vista Horace Mann K-8 Community School, John O’Connell High School and Mission High School– participated in the survey. While the survey is anonymous, we collect core demographic data from respondents:

- 25% of respondents were in middle school, 75% in high school

- 40% of respondents identified as female, 56% male and 4% nonbinary/gender non-conforming

- 68% of students identified as Latino

- 11% of students answered the survey in Spanish

The following sections present the key findings from the 2022 School Climate Survey across four domains: School Safety; College Readiness; Internet and Technology Access; and Home Life.

School SafetyOur student respondents largely feel safe and supported in their school settings; however, when we disaggregate survey responses by age and gender, we see some disparate experiences among MPN students – disparate experiences that merit further inquiry.

The vast majority of survey respondents indicated that their school was a supportive environment: Eighty-one percent agreed that there was at least one teacher or staff member on whom they could rely, and 77% felt that staff and teachers treat students with respect. As Figure 1 shows, over two-thirds of MPN students feel safe at school, and traveling to/from school; however, high schoolers report feeling less safe traveling to/from school compared to middle schoolers, and are less inclined to report having a school staff member on whom they could rely. Conversely, middle schoolers were less likely to report that teachers and school personnel treat students with respect.

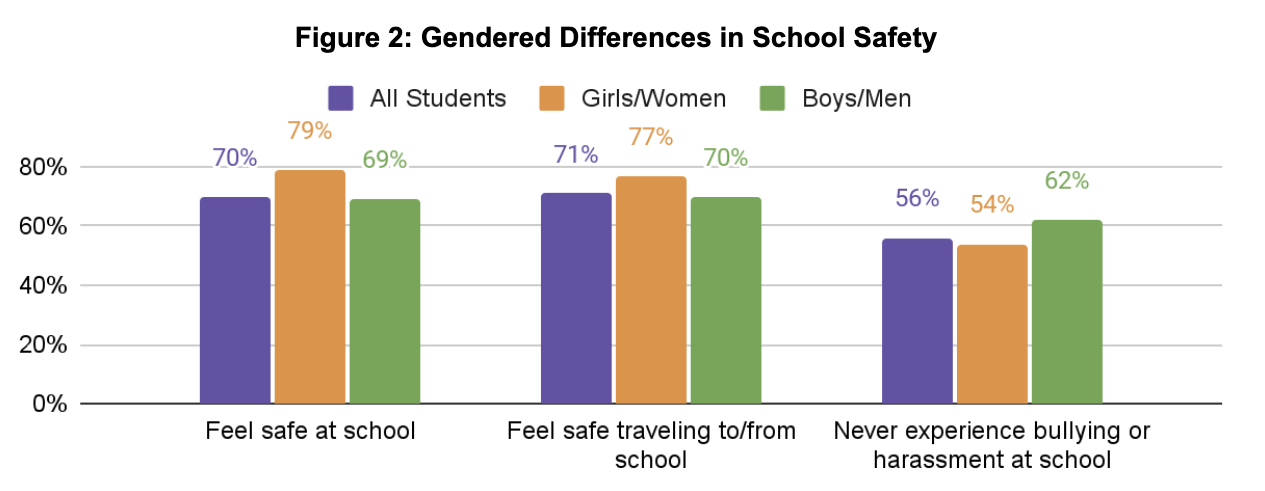

Figure 1: MPN Student Perceptions of School SafetyWhen disaggregating the data by gender, we noticed that female students are more likely to report that they have experienced bullying or harassment (see Figure 2). However, there was a contrary trend in the school safety data: Girls were more likely to report feeling safer at school and traveling to/from school than male survey-takers.

Figure 2: Gendered Differences in School SafetyAs the SCS is almost entirely multiple choice, we can only speculate why these statistical differences emerged in the data. For instance, it is possible that high schoolers feel less safe between home and school because they are less likely than middle schoolers to get a ride from their parents; and there is a chance that boys are simply less likely to report that they have been bullied, out of a sense of pride. These are intriguing findings that we will need to research further to understand more clearly.

College ReadinessThe majority of MPN students who took the SCS intend to pursue higher education; however, disaggregating the survey responses reveals that Latino and male students are less likely and less confident in seeing college as part of their future.

Over two-thirds (69%) of MPN students plan to attend a four-year college, either straight from high school or as community college transfers; however, only 62% of boys/men in high school noted that they plan to attend college, compared to 90% of girls/women. As a whole, women in the U.S. are more likely to attend college than men; however, the nationwide gender imbalance in college students is nowhere near what we see in the SCS data.

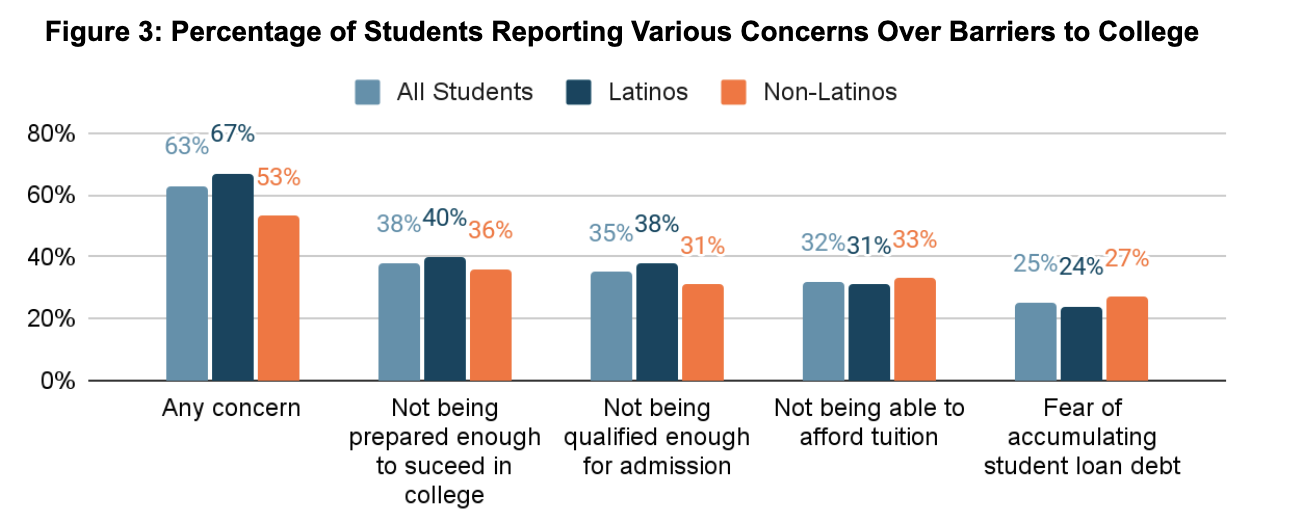

While a majority of MPN students, regardless of gender, intend to earn a bachelor’s, Latino students were far likelier than non-Latino students to report uncertainty about their ability to attend and/or succeed in college. Half of non-Latino respondents noted that they were confident in their ability to go to college, compared to just one-third of Latinos. Per Figure 3, Latino students were also more likely to report their concerns over an array of specific barriers to college success, from academic preparation to financial capability.

Figure 3: Percentage of Students Reporting Various Concerns Over Barriers to CollegeThe School Climate Survey also asked respondents to name any specific resources they thought would help them succeed in college. Notably, the most frequently cited response was access to mental health resources – perhaps an indicator of the psychological stressors youth have faced during the COVID-19 pandemic, and/or widespread understanding about the benefits of mental health care. Other common responses ranged from additional academic support to financial aid to peer mentorship.

As with the data on school safety, we will need to explore in greater detail why there was such an imbalance between male and female respondents regarding their college plans, what else MPN partners can do to support Latino students on their pathways to college and what kinds of mental health supports would best help MPN students in postsecondary education.

Internet and Technology Access Remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic laid bare the importance of equitable access to the internet and computing devices at home. Disparate quality in home internet and personal computers could exacerbate systemic disparities in achievement for students from low-income families.

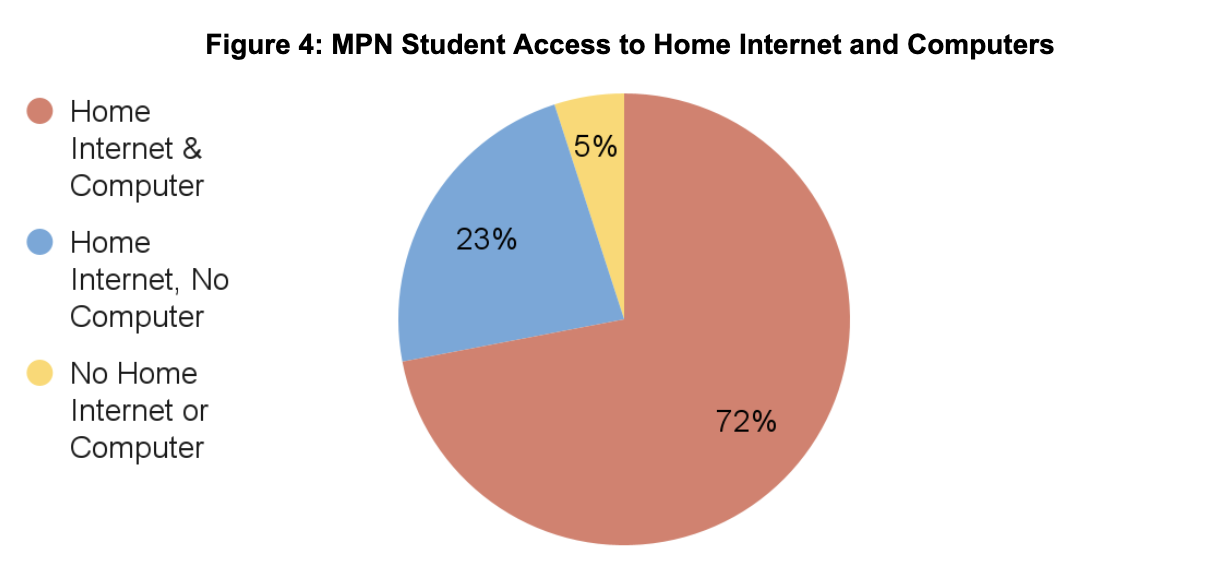

As Figure 4 below shows, nearly all (95%) MPN students have access to the internet at home; however, over one-quarter (28%) of respondents do not have access to a home computer or laptop. Students with home internet but no home computer reported that they could access the internet through their smartphone, a tablet device and/or a video game console instead. Compared to a computer, none of those devices are optimal for students to complete homework, write essays or apply to jobs/colleges.

Figure 4: MPN Student Access to Home Internet and ComputersIn this context, MPN partners could connect students without home computers and internet to onsite technology, or work with families to secure access to low-cost computing devices and internet subsidies.

Home LifeFinally, the SCS asks students about a few components of their home life and daily activities.

- Nutrition: The majority (83%) of students eat two or more servings of fruit and vegetables a day; however, only 18% meet the Department of Education’s (DOE) benchmark of five-plus servings a day.

- Exercise: The majority (86%) of students are engaging in regular physical activity; however, only 27% meet the DOE benchmark of 60+ minutes of daily physical activity, and even fewer Latino students meet this benchmark (19%).

- Student Mobility: Three-quarters (73%) of MPN students have lived in the same home for the past year; however, 13% of students report having moved two or more times in the past year, which can disrupt students’ ability to learn. This is of particular concern in the Bay Area, where the housing crisis imperils many low-income families and their living situations.

Conclusion and Next StepsOverall, the SCS reveals positive trends: The majority of MPN students feel safe at school, intend to go to college and do not face housing instability. In contrast, we can also see disparities in the experiences of male and female students, and Latino and non-Latino youth. It will be important for us to delve deeper into these trends, as well as the other challenges and barriers that our respondents named.

Data from the SCS serves as a foundation for additional exploration. Because the survey is only 18 questions and mostly multiple choice, we would benefit from different kinds of data activities with students, families, MPN staff and school personnel to better understand some of the findings from this year’s survey data. For instance, we could explore further:

- Why do high schoolers feel less safe traveling to/from school?

- Why do female students feel safer, even though they experience more harassment?

- Why are male MPN high schoolers far less likely to plan to attend college?

- Why are Latinos less confident in their ability to attend college?

- Why are mental health resources the most commonly cited need for college?

We are excited to dive deeper into these questions and learn the context for them in future analyses, including longitudinal analyses, and comparisons to statewide and national data. Be on the lookout for further analyses posted here, as well as updates on our work based on this year’s survey data.

______________________________

[1] Ninth-graders are not represented among the survey population, which is a trend evident in past years’ responses and is reflective of who participates in the high school Beacon Center programs. James Lick Middle School students were unable to participate this year due to logistical challenges with survey administration.